As urbanization accelerates, both elderly people living alone and younger generations increasingly seek companionship from animals. Companion animals have become important members of many households. According to statistics, China now has approximately 150 million companion animals and nearly 70 million pet owners. In May 2020, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs released the National Livestock and Poultry Genetic Resources Catalog, formally reclassifying cats and dogs as companion animals rather than traditional livestock. As the pet market continues to expand – and in the absence of comprehensive anti-cruelty legislation – many issues remain unresolved.

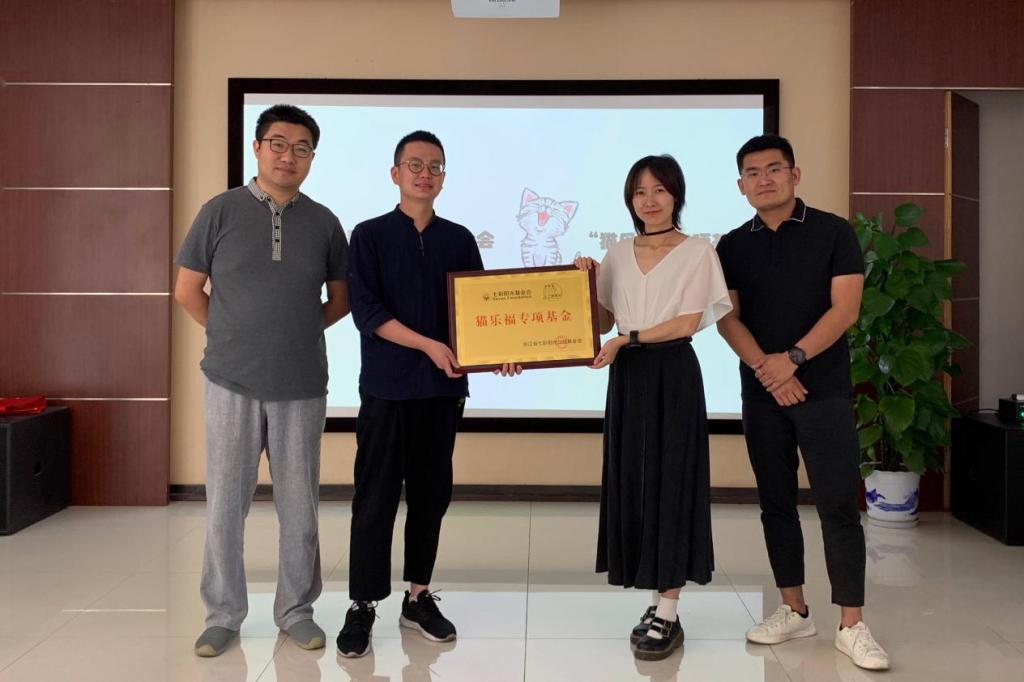

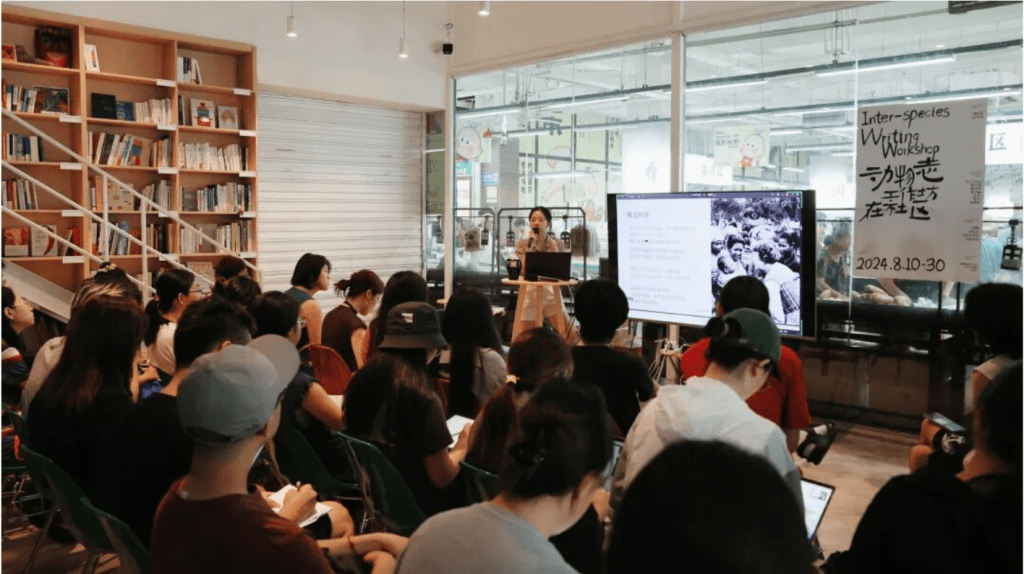

In August this year, Elefam , in collaboration with Dacheng Xiaocun and PIDAN, launched the Inter-species Writings Workshop in Chengdu’s Beilei Community. Through lectures, field observation, community-based learning, and on-site writing, the workshop offered practitioners, enthusiasts, community residents, public-interest workers, community builders, creators, and the broader public an integrated curriculum on animal protection and ethics.

In August 2024, I traveled to Chengdu’s Beilei Community to participate in the “Animals in Community: Inter-species Writings Workshop.” The phrase Inter-species writing workshop on the poster first grabbed my attention. I was especially curious: how could nonfiction-oriented methods – observation, interviewing, writing – be woven into public-interest advocacy?

The program consisted of three parts: theoretical lectures, fieldwork in Chengdu, and nonfiction writing. Participants could join flexibly, online or offline, for the full program or individual sessions.

The online lecture, “The Trajectory of Multispecies Ethnography,” was a conversation between Oxford anthropologist Eben Kirksey, UCL anthropology PhD Yang Bo, and LSE anthropology PhD Zhou Yufei. Kirksey argued that multispecies anthropology moves beyond traditional anthropology’s human-centered lens to foreground the entangled relationships between humans and other life forms.

Wang Po, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Shandong Normal University and translator of Animal Communities, introduced the history and current state of animal ethics, outlining how ethicists around the world argue for animal rights. Through global examples of multispecies communities, he posed a sharper question: How can we pursue animal rights in a non-ideal world?

Meanwhile, Princeton PhD and Arizona State University professor Chen Huaiyu approached the subject through religion, examining how Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, and folk beliefs shaped animal representations in medieval China – and how cultural residues hide behind vivid animal tales in Buddhist scriptures. As he wrote in “The Origins and Aims of Animal History”:

“European natural history centers on ‘nature’; Chinese natural studies center on ‘things’… The study of animals in Chinese natural history should be understood as premodern historiography – philological research aiming to classify and understand animals.”

With interdisciplinary theory in place, field practice became even more essential.

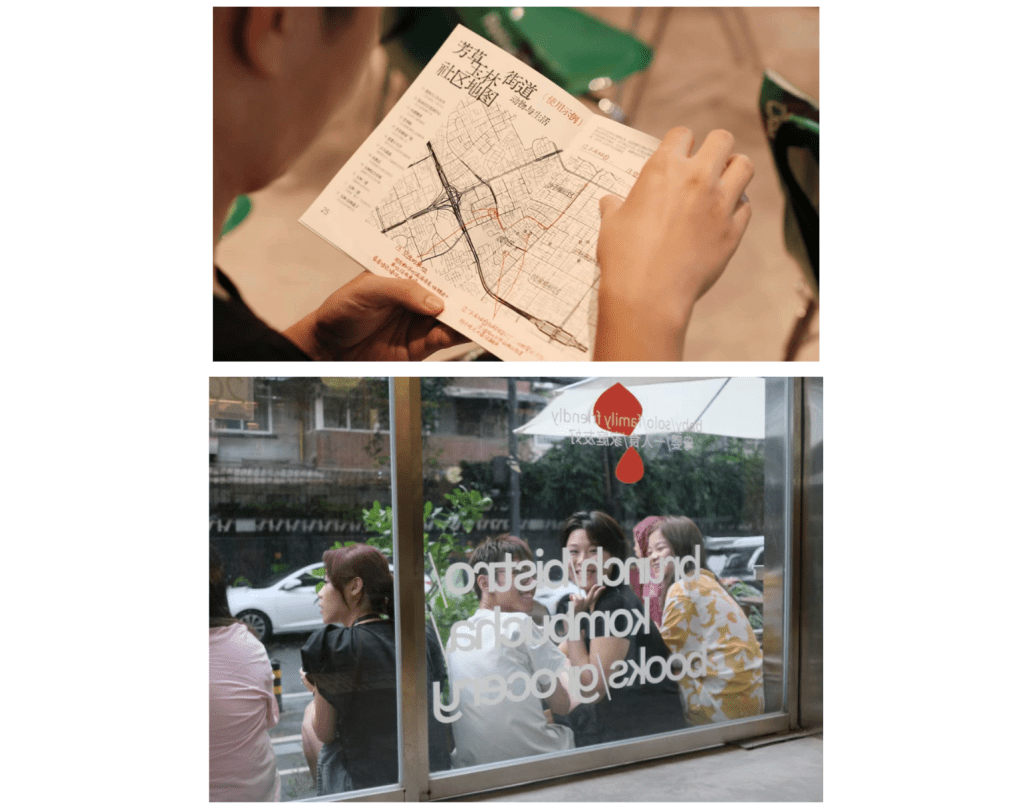

The offline sessions were held in Chengdu’s Beilei Community, a well-known example of community revitalization—part of the broader “Yulin” area familiar to many visitors. Inside this revived neighborhood, shared creative spaces, lively weekend markets, and animal-friendly zones created fertile ground for a workshop centered on coexistence and co-creation.

Classes took place in a café adjacent to the Beilei farmer’s market. A bright floor-to-ceiling window split the everyday bustle of the market from the curated aesthetic of the café. Through the glass, one could see Chengdu aunties carrying their baskets through the redesigned market; inside, writers, animal advocates, designers, and social workers gathered to explore the lives of companion and community animals through anthropology, nonfiction writing, art, and fieldwork.

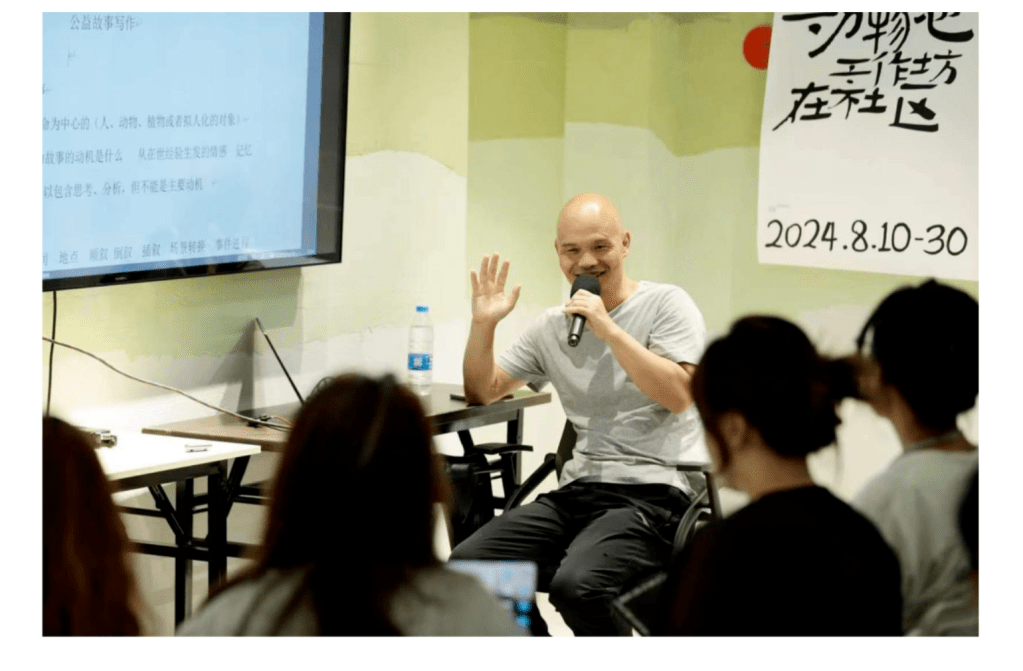

Nonfiction writer Yuan Ling delivered a talk on “Animals in Nonfiction Writing.” Having grown up in rural Shaanxi, Yuan drew from real encounters between villagers and wildlife, and between families and their dogs. In his work, even the harshest realities contain tenderness:

“My cousin leaped across the stream first, then stretched out his hand to pull me over. The dog hesitated, my cousin crouched down and reached out as he had to me – so the dog jumped too…”

Beyond theory, Yuan acted as a field mentor – guiding students through interviews while quietly observing the community’s everyday human–animal interactions.

LSE anthropologist Zhou Yufei, whose award-winning nonfiction chronicles two years of fieldwork in Tibetan regions—working in dog shelters, assisting with births, speaking with herders—accompanied participants throughout the workshop. She emphasized learning not only from people but also from animals themselves:

“Take what human teachers give you, but approach the animals and see how they respond.”

Workshop director Pan Xueyun explained the program’s intention:

“Even with anthropology, religion, humanities theory, and community animal governance in place, I still hoped the final output would be a story. Effective public advocacy cannot rely solely on didactic messaging – it must come from real interactions between humans and animals. Nonfiction is powerful in this way.”

Participants engaged in community walks to observe resident–animal relationships. Whether chatting with an uncle walking his dog or an elderly woman feeding stray cats, students encountered deeply memorable stories.

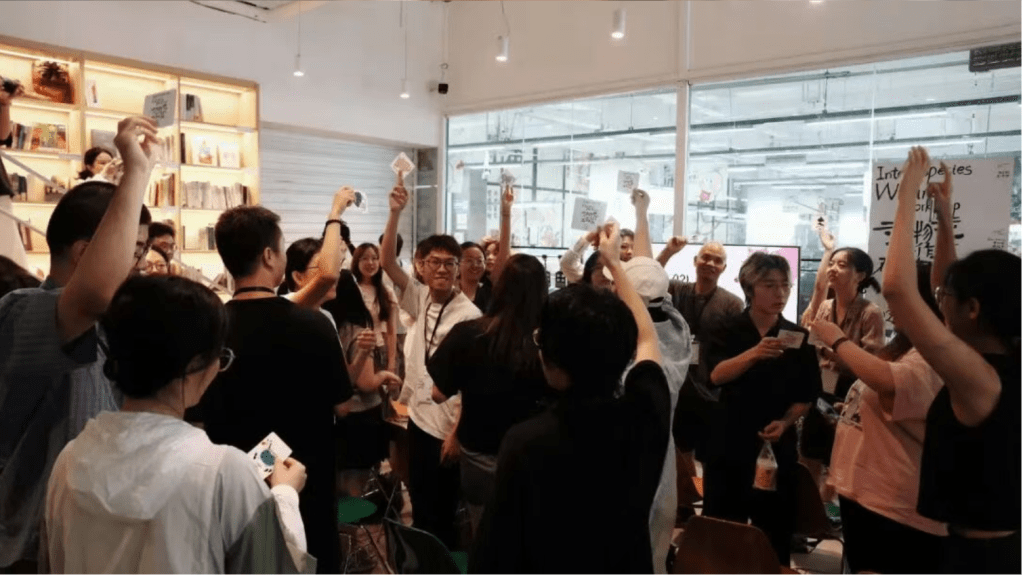

A “shared recipe for people and pets” activity highlighted the connection between caring for animals and caring for oneself. A class on dog behavior brought local residents and their pets into the workshop, making the space lively and participatory.

During the final day, participants attended a talk by Taiwanese scholar Chien Yung-hsiang. When one attendee’s cat showed signs of stress, several workshop students gently raised a question during the event:

In promoting “pet-friendly” spaces, are we prioritizing human desires over animals’ own needs?

After the workshop, participant Wu Yi submitted a nonfiction piece titled Lives in the Corners of the City, documenting the story of Beilei’s “cat granny” who cares for community cats.

“During fieldwork, I found myself shifting from observer to listener, even participant. Feeding cats together became a passageway into another person’s world, and writing was the only way to honor that experience.”

The Inter-species Writings Workshop showed how interdisciplinary knowledge, field immersion, and storytelling can deepen public understanding of human–animal relationships. It offered not only technical knowledge in ethics and conservation but also emotional insight—reminding us that protecting animals begins with seeing, listening, and writing with care.

Text by Ming Xingchen, Writer/Contributor.

- Primary Focus: Non-fiction reporting/journalism.

- Areas of Work: Interviews and profiles, cultural reporting, and commentary writing.

- Specialization: Dedicated to collecting and documenting fascinating local customs and the preservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) across various regions.